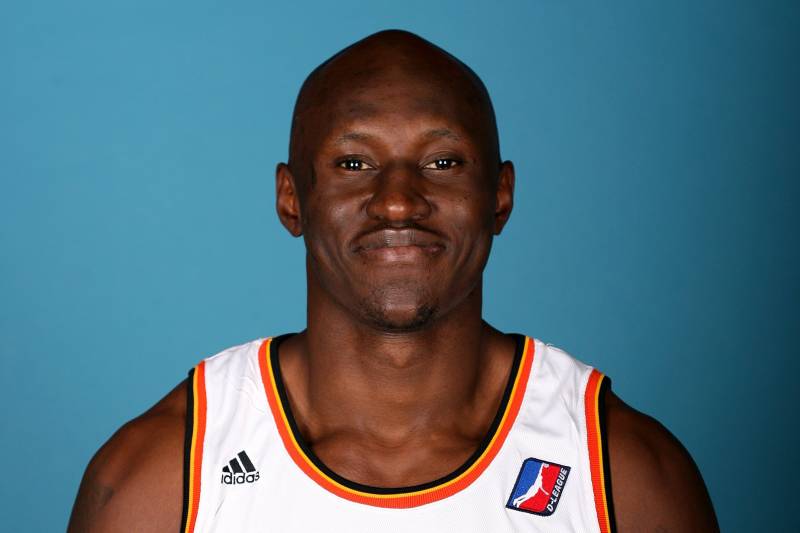

Ejike Ugboaja has high hopes as 2019 Summer Camp draws close

April 23, 2019Before he embarked upon a basketball career that ultimately helped him get drafted into the NBA, Ejike Ugboaja’s future resembled one that most of the kids in his home country of Nigeria still face today. Sports were his way out of a nation that's still grappling with economic and social hardships that leave most children with few options other than avenues full of negative consequences.

One decade after leaving Nigeria, Ugboaja is making it his life’s work to ensure more kids from his homeland get the same opportunity.

“I came from a less fortunate background. For me to do this is something I’ve always wanted to do: to give back to my home country,” Ugboaja told Bleacher Report recently. “When I was drafted into the NBA, one of my main goals was to find a way to give back to Nigeria. When I got that opportunity, I just was fortunate to find a way to make it work.”

The 6’9”, 225-pound power forward, who was drafted by the Cleveland Cavaliers in the second round of the 2006 NBA draft, never played a regular-season game in the NBA. Instead, the majority of his career has been spent playing in Europe and for Nigeria’s Olympic national team. Through the Ejike Ugboaja Foundation—which is a nonprofit organization he started in 2006—he and his brother Henry are helping young athletes in Nigeria find opportunities to play basketball and football in the United States.

In the latter sport, his camp is responsible for establishing Nigeria as the next frontier in college football recruiting.

“The bottom line is that if we see a school that said we have scholarship openings for soccer or another sport, we jump into it,” Henry said. “So for us, sports became the motivating factor to help these kids back home. Most of them, if you hear their stories in terms of finance or family background, you’d be amazed that they have made it here. I think that is what touches us.”

While his background is in basketball, Ejike and his brother have put together a camp that has seen more than 15 football players sign scholarships to FBS schools since its first run in 2010. Additionally, hundreds more have been able to attend high schools in the United States thanks to the foundation's efforts. When the athletes do make it to the U.S., the foundation uses its resources to help cover their living expenses.

The camp’s foray into football came about almost by accident, with a keen observation by the brothers recognizing traits in Nigerian athletes that could translate favorably into America’s most popular sport.

“As word spread through Nigeria that basically this is your way out and to the United States, they started getting a number of kids to show up to these camps or all-sports tryouts,” explained Erik Richards, who is the national recruiting director of the U.S. Army All-American Bowl. “What [Ejike and Henry] noticed is they had a few 6’6”, 300-pound kids showing up. They weren’t tall enough for basketball. They weren’t short and nimble enough for soccer.”

That’s when football entered the equation.

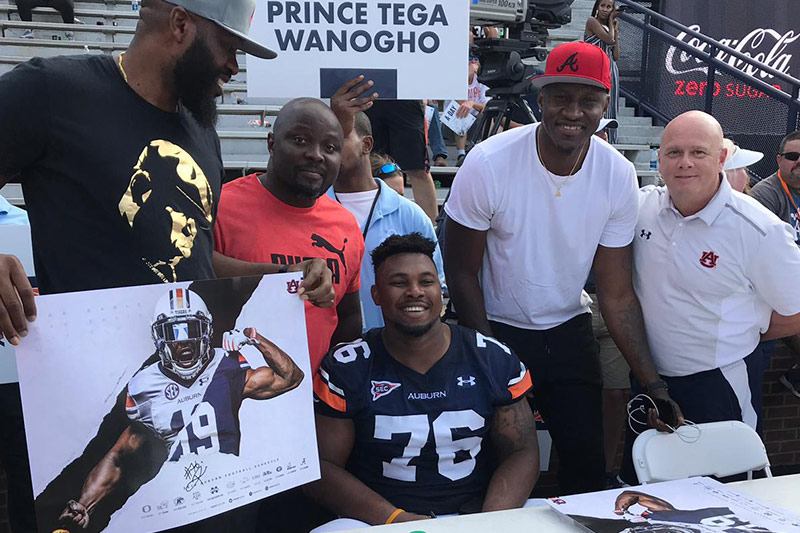

Over the years, Ugboaja’s camp has been the breeding ground that has produced notable talents such as current LSU offensive lineman Chidi Valentine-Okeke, Florida State offensive lineman Abdul Bello and Auburn defensive lineman Prince Tega Wanogho. Current USC early enrollee Oluwole Betiku—the nation’s top weak-side defensive end prospect in the 2016 cycle—is another athlete who became a household name in recruiting circles after leaving his hometown of Lagos just two years ago.

As young kids in West Africa are learning more about the game and seeing their former peers find success in America, Ejike and Henry are hoping those gains open the doors for more athletes to find similar opportunities in the future. Players such as Valentine-Okeke, Bello and Betiku can thank Sunny Odogwu for helping Ejike and Henry discover the game of football.

Odogwu left Ejike’s summer camp in 2009 bound for the U.S. to play basketball at Victory Christian Academy in Conyers, Georgia. According to Matt Porter of the Palm Beach Post, he bounced around to different schools for basketball until one of his coaches suggested he try out for football. Ejike vividly remembers the phone call in which Odogwu explained he would switch gears in his athletic career.

“I asked him, ‘are you sure?’ He said, ‘Bro, I think I will do it,’” Ejike explained. “So he gave it a try. For me to see how quick he came around, I was like, ‘damn, this is amazing.’”

Odogwu eventually landed a scholarship to the University of Miami as an offensive lineman. He will be a redshirt junior this fall and is currently the starting right tackle for the Hurricanes, per Ourlads.

Buoyed by the interest in Odogwu from football coaches during his recruitment, Ejike and Henry started the process of attracting football coaches to come and help them teach the game at their annual summer camp.

Odogwu’s success inspired kids in Nigeria to learn more about the game of football, and Ejike’s camp quickly became the event that helped to bridge that gap.

“It’s surprising to me because it’s taken off so fast. We never expected it to grow this much this soon,” Ejike said. “I was thinking basketball was the one thing that everyone would warm up to. But when Sunny switched to football, a lot of people saw the progression he made in football. They see that his future is now in the game of football.”

Getting their athletes to the United States is a mission in and of itself.

Henry, who is an adjunct professor at Ohio Mid-Western College and teaches business and marketing classes, also worked as an educator and admissions counselor in Nigeria.

As he explained, he routinely worked hand in hand with the U.S. Embassy in clerical matters—which has aided the brothers in helping kids earn visas for entry into the United States.

“I started dealing with those [visa and paperwork] issues,” Henry said. “I figure out the details on each kid and what grade they are supposed to be in, and I work with each school in verifying paperwork and figuring out the proper area to place them academically. Sometimes when colleges have trouble figuring out the translation of the transcript, I help them sort that out.”

Richards notes that because of their typical two-year visa statuses upon entering the country, in most cases, the only way they are eligible to compete in prep sports in the U.S. is for them to attend private schools. In most cases, the school helps locate a host family. In some instances, Henry and Ejike use their resources and connection to find a host family for the kids.

“The majority [of the Nigerian athletes] that come over have to be enrolled in a charter school. That’s why a lot of them end up at private schools,” Richards explained. “Most of these kids are 16, 17 or 18 years old and starting their junior year of high school. To go through the whole [host] process is strenuous, and by the time they get done, they are already done with high school.”

While eligibility concerns are prevalent with foreign athletes in the recruiting process, the problems that arise have more to do with language and academic classification than the kids’ ability to thrive in a new learning environment.

“These kids are very academically enriched, believe it or not,” Richards said. “Some kids can speak four, five or six different languages. [Most times] when they go to take the test at schools on where to place them [eligibility-wise], they are beyond being a freshman or a sophomore.”

Still, even when kids are able to make it to the United States and graduate to being on the doorstep of making their dreams come true, another set of challenges awaits them.

In addition to having to learn a new sport in a foreign country, the two factors that are often the toughest for these players are the culture gap and being away from their loved ones.

While he was busy racing up the recruiting ranks, Betiku explained the psychological toll that being separated from his family has created for him since he’s been in the U.S.

“Sometimes, I feel kind of sad,” Betiku said. “[My family] don’t know about the camps and everything. I try my best to explain everything. I try to stay motivated. My school family, they all love me. My coaches, everyone that has supported me to this day, I think about them. They are counting on me to do great. My mom, I just tell her I did really good, so she’s happy. That’s why I do what I do.”

Valentine-Okeke, who is a redshirt freshman and will compete for a starting job at LSU in the spring, admits his journey to Baton Rouge has had its ups and downs.

Still, he knows he’s one of the fortunate young athletes to have the chance to get a free education at a top university such as LSU.

“I always watched football back home. I didn’t have someone there to coach me or tell me about the game,” Valentine-Okeke said. “But I did have a passion for it when I watched it. It happens to be one of the games that they introduced in Nigeria then. I was lucky to be a part of it.”

Both Ejike and Henry have continued to play a pivotal role in helping him since he’s arrived in the U.S.

In fact, Henry serves as his guardian.

“[Ejike and Henry] know my family back home in Nigeria,” Valentine-Okeke said. “I lived with Ejike when I was going to school in Georgia. When we have breaks, I go to Georgia with him or Ohio with Henry. We have a great relationship, and they have really helped me a lot.” Richards recalls learning of Valentine-Okeke’s story when the offensive tackle was on the camp circuit as a recruit.

He and Bello, who were both in the 2015 class, were performing well at spring and summer camps against the nation’s top defensive linemen despite minimal experience.

Richards surmises that their inexperience can be turned into a positive by coaches eager help them reach their enormous upside.

“When a coach starts out with them, they are so attentive in wanting to learn the right technique, that you don’t have to unscrew everything,” Richards said. “For these offensive line coaches at these camps, it’s very easy to mold them very quickly because they have nothing. It’s like you are not having to teach an old dog new tricks. They are starting at zero.”

In each of the examples of players such as Bello, Betiku, Wanogho and Valentine-Okeke, their recruitments exploded with offers from top programs from coast to coast.

Valentine-Okeke said there are plenty of athletes in the West African nation whose talents are comparable to his and the other players' abilities who have found success since taking up the game.

“[There are] a lot of kids like me and even some who are better than me back home,” he said. “I know they have what it takes to make it here. If they believe and work hard, they can come over here and make it to college.”

Ejike and Henry share that belief, which is why they have plans on expanding the camp’s reach.

Ejike notes registration for the camp may reach to over 1,000 athletes, with the foundation’s goal of bringing at least 20 players to the U.S. from this summer’s camp—of course assuming they find enough skilled players and enough schools stateside willing to provide scholarships for them.

From a recruiting standpoint, Richards said there’s a bit of hesitation at first from college coaches because of concerns over eligibility. However, given the success of this first wave of Nigerian imports, he expects the trend and interest to only grow in foreign prospects.

“What I see happening after these guys have some success in the next few years, then the college coaches will come around and start taking chances because with these kids it’s not your typical recruiting cycle where you get to follow him from his freshman year on up,” Richards said. As the camp’s stature continues to grow, so do the opportunities for young kids who otherwise wouldn’t have a chance to attend universities as prestigious as the ones in the United States.

Regardless of whether the players go on to have NFL careers, in the minds of Ejike and Henry, the real gratification comes with helping kids create opportunities that can change the course of their own lives, as well as their families' lives back home.

The two brothers have dedicated their time, resources and energy to helping young athletes from their homeland turn hopes into a new reality. All the while, they haven’t lost focus on giving back to the communities that raised them.

With each athlete who gets a scholarship, the outlook for the next generation of athletes in Nigeria becomes brighter.

“I think the biggest thing the focus needs to be on here are two brothers that were afforded the opportunity to come over here, and they are doing a lot of good for kids hoping for a similar opportunity,” Richards said. “I think that is a testament to them and what they are about. It’s amazing that these guys have made this their calling in life to help these kids live a better life.”

This article first appeared on Bleacher's Report.